Excavation

artifact / ärdəfakt /

noun: an object made by a human being, typically an item of cultural or historical interest.

archeology / ärkēˈäləjē /

noun: the study of human history and prehistory through the excavation of sites and the analysis of artifacts and other physical remains.

Experience

Wine can represent many things, like a particular flavor, a palatal experience, the time and efforts of cultivation, or the intellectual design of a product. And we can talk about it in so many ways too, evaluating wines geographically, aesthetically, linearly, horizontally. We use metaphor. We use qualitative biochemical data. We use narrative, and we attach it to a physical object destined for consumption, consume it, and begin to evaluate based on an array of potential methods of inquiry. If we are to treat the appreciation of wine in any academic way, that is to study it, we first must choose the method and scope of inquiry, which for me, particularly regarding older bottles, skews to the archeological.

Throughout my time at Paul Marcus Wines I was fortunate to taste, with some regularity, wines that far surpassed me in age and maturity. Over the past few years I’ve seen a surge in interest, enthusiasm, and availability of more obscure wines like this (18 year-old Sancerre Rouge, 28 year-old Portuguese Arinto, 30 year-old Santa Cruz Cabernet), wines that have taken on the secondary and tertiary characteristics of graceful development. Right away you can recognize acidity and color, defining characteristics of longevity, the ability to stay fresh, and the availability of concentrated fruit. But always, wines like these come with a caveat, a disclaimer of sorts about provenance, about transportation, storage, preservation, the guarantee on untainted products, the artifacts we so casually imbibe. So what can the study (and appreciation) of these agricultural remains signify about history? Perhaps that it inevitably devours itself.

Vineyard at Villa Era, Alto Piemonte

Visiting Piemonte

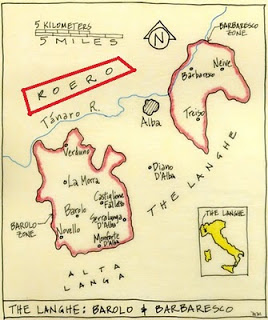

Last November, I was invited to Italy by the business consortium and viticultural association of Beilla, a small sub-region of the Alto Piemonte, west of Milan and almost to the Alps. It is an absolutely beautiful area, richin chestnuts, risotto, and an earnest wool milling industry. Right now, the region is in the process of redefining itself as a premium growing and production zone for grapes, particularly Nebbiolo. Today about 1,500 hectares of vines are planted in Alto Piemonte, primarily to Nebbiolo, though small amounts of Vespolina, Croatina, Uva Rara and Erbaluce are also planted. In 1900, however, over 40,000 hectares of grapes filled the region, a gross historical disparity which the winemakers there hope to resolve. The cool temperatures, extended sunlight exposure from altitude, latitude, and proximity to the Alps, and the geological event in which a volcano upended a mountain to expose ancient marine soils, all contribute to the severe minerality, acidity, and vivid coloration and red flavor of these Nebbiolo wines. Although the Langhe in the more southern part of Piedmont carries more commercial and critical weight in the industry now, the sheer volume of wine produced in the heyday of Alto Piemonte, and the evaluative quality of that wine, can shed light on both the cultural and natural history of the area. Touring vineyards and wineries, attending a seminar on soil types, tasting recent releases of wines from a dozen Alto Piemontese producers, and eating beautifully from the local farms and tables were all illuminating aspects of the culture and the cuisine and the heritage of the region, but nothing taught me more than tasting through a series of library bottles from four small wineries. It was easily the most personally revealing experience I’ve ever had with wine.

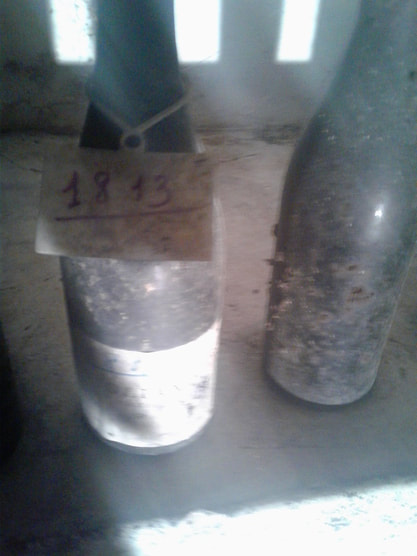

Before the tasting at Villa Era, a tiny producer in midst of laborious reclamation of vineyard sites from a century or so of forest encroachment, we toured the cellars (as we had the previous evening at Castello di Castellengo) to see the dusty, cobwebbed and moldy bottles of mismatched shape and size with tags and decomposing labels that date these artifacts through the past several centuries. These library collections of estate bottlings provide evidence that throughout time the properties yielded a product worth preserving in glass, underground in stable conditions, on the assumption that someday, someone would recognize that this was a fine wine designed to shine for future generations.

Bottles in the cellar at Villa Era, Alto Piemonte

Experiencing Aged Piemonte

The oldest artifact was a bottle of 1842 Castello di Montecavallo which is almost impossible to describe ingesting other than physical euphoria a, sensation of emotionally charged discovery. To share this piece of completely vibrant, assertive history, with the current generations of folks who farm the same land produced in me this neurological firing where I tried to connect pure sensory experience with the particular circumstance and somehow try to intellectually remember that this wine was deemed over the course of 175 years to be worth preserving, and that this gorgeous and completely unexpected semi-sweet but citric and lively wine five times my age was now going to be absorbed by my body. It felt as though I’d consumed an ephemeral dose of wisdom.

I know that’s hard to qualify. But trying to compare, or at least comprehend, the 1896 Castellengo and 1897 Villa Era was somewhat more grounded. I’d been in these cellars, walked in these vineyards; I was sitting in the building where 120 years earlier one of these wines had probably just finished fermenting, maybe just gone into barrel. One was reddish and slightly tannic, the other golden and slippery, and both were fresh. So you speculate. The grape, the vintage, the design? Two wines made a year apart within ten kilometers of each other and yet so fantastically different. And still with this surreal recognition that these wines were made around the time that my ancestors left Europe to participate in a different history a continent away.

Tasting a pair of wines, 1931 Montecavallo and 1934 Castellengo, I could sense some greater intensity, whether to do with process development or a renewed artisanal concentration in the wines after the industry fallout in the first decade of the 20th Century due to climate and disease, I don’t know. But the Montecavallo, like the 1842, offered a pure, sandy, pear-like quality, and the Castellengo, like the 1896, was denser, richer in color. The 1934 showed great definition as Nebbiolo, herbal, brilliant red, tannic and tough like a the skin of a wizened crabapple, a gorgeous wine and my favorite of the entire tasting.

Modern Respects

The more recent presentations, a 1960 from Villa Era, and a 1965 and 1970 from Tenuta Sella, a producer PMW has recently carried, proved a welcome familiarity, more within the bounds of my previous experience. These were wines with structure, ripe and dusty fruit and emphatic texture. These were wines wound with youth, wines that I expected to develop further. In the Sella wines, particularly, a continuously operating producer since the 17th Century, I tasted exuberance, a great and yet unrevealed potential. I felt aligned with Nebbiolo, a tart little corner of recognition on my palate, but I also felt the resonance of timbre, a uniformity, or at least a seam of connective tissue that stitched me to the place, to the people, to the things this circumstance in time and culture had revealed.

Tenuta Sella 1965 Lessona & 1970 Lessona

And then after sharing a bottle of the 2010 Sella Lessona over dinner back in California, and talking and laughing and telling the story, exposing the narrative and presenting the evidence, one can still only project the future. We have what we have and we have what has been preserved and with that we have to make do. I know that in Alto Piemonte they used to make great wine and that over time the wines changed and adapted and that now by looking back, it is also possible to look forward, to understand the history and prehistory of a specific place, the culture of past, present and future through artifacts.

(credit: Patrick Newson)